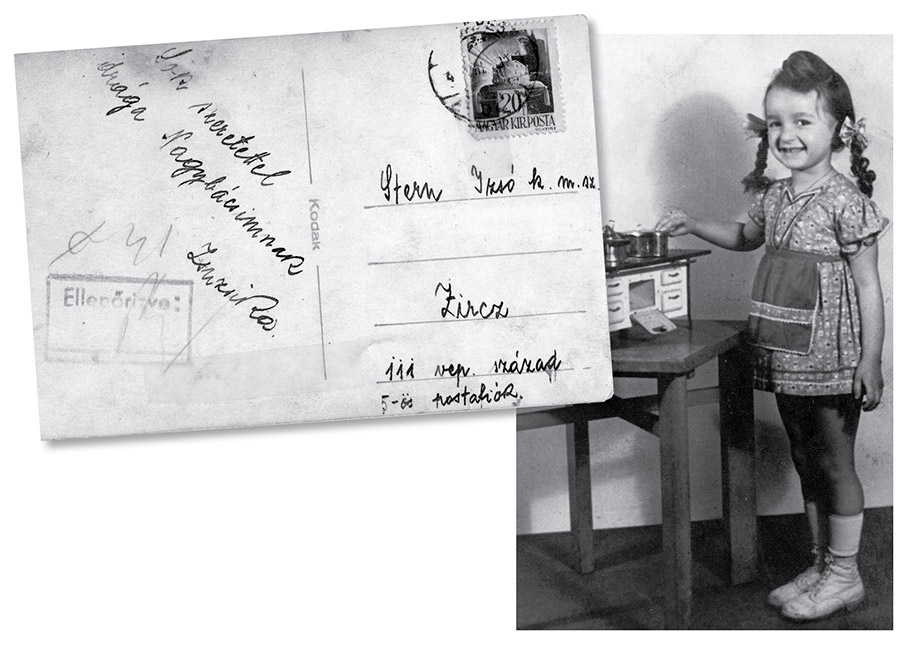

When Zsuzsika Rubin was four years old, her mother, Lilly, took her to a photographer’s portrait studio, where she wore different outfits and hairstyles and struck poses with props: as an all-grown-up lady doing her “daily shopping” with a plush dog and a straw basket, as a housewife in an apron hovering over a little toy stove. The two shots became postcards, one sent to Lilly’s sister Magda in France, another to her brother Izsó, who was in a forced-labor camp in Zircz in northwestern Hungary. The postcard to Izsó is undated, but the one to Magda—who had not yet met her niece—is dated February 14, 1944. Zsuzsika’s father was at a forced-labor camp himself, in Russia, though he returned home to Budapest five days before Lilly sent the postcard to her sister.

“To my sweet good Magduska, with much love and many kisses from little Zsuzsika,” wrote Lilly in Hungarian. “With much love to my dear uncle,” she wrote to her brother, signing it as Zsuzsika. A lifetime later, Zsuzsika, now Susan Rubin Suleiman, a professor emerita of French and comparative literature at Harvard, notes that the photography studio from her session as a little girl was called Mosoly Albuma, Album of Smiles. “At least some people were still smiling in Budapest in February 1944,” she writes in her new memoir.

Germany invaded Hungary the following month, to ensure the country didn’t desert its by-then tenuous alliance, and—Suleiman’s dry wit continues—to “take care, at last, of the Hungarian Jews,” the last Jewish community in Europe. Between spring of 1944 and liberation by the Soviet army a year later, more than half a million Hungarian Jews were killed. The Jews of Budapest, like the Rubins, lived in relative safety until the fall of 1944, when Hungarian’s fascist and passionately antisemitic Arrow Cross Party (Nyilaskeresztes Párt) came to power. In February 1944, while young Zsuzsika was sweetly posing for a photographer, Hungarian Jewry was on the brink of terror and death.

…

Suleiman has said she drafted Daughter of History during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic “at a time when there seemed to be nowhere else to go but inward,” and she uses mementos like the surreally cheery photo postcards to dive into her childhood in Hungary and her young adult years in America. … Read the rest at Jewish Review of Books

Photos courtesy of Susan Rubin Suleiman